Scaling Product Security Across the Org

Toby Irvine

Your security team is overloaded. There are barely enough hours in the day to keep up with incoming requests, let alone improve ways of working. What's the cause of this?

The Ratio

In our work with large organisations we’ve developed a “rule of thumb” that quite usefully predicts the proportion of development and cybersecurity staff in the workforce. For companies whose primary business isn’t software development but have internal, established application delivery capability (banks, telcos, etc.) around 10% of the workforce are software developers.

At the scale these organisations operate at, typically an architecture function has split off from engineering and is around 10% of the developer total. Cybersecurity also has a dedicated function within the business that is 1% of the developer total. So for every 100 developers, there is one security professional.

It’d be useful to put some real numbers on that. A global organisation with 250,000 staff will have roughly 25,000 software developers, 2,500 architects and 250 cybersecurity professionals. I’d be interested to hear of any substantial outliers to this ratio if anyone reading knows of any. Correct my assumptions in the comments below!

Let’s take a look at those proportions visually:

Pretty hard to see the cybersecurity folk down there. My apologies to Everyone Else, you are very important from a cybersecurity point of view but for the purposes of this article on application security I’m going to ignore you so we can see things better.

That’s better. Now, removing cybersecurity and architecture from day-to-day delivery of application changes collects domain experts together and, typically, charges them with assessing and authorising changes to systems from the aspect that their domain covers (security/system design). This is what ITIL calls Change Advisory Boards (CABs). A great concept to manage change in principle, and it’s proven very useful in other industries, but in application development it has a proven drawback: it just doesn’t work at all.

From the analysis of several years of research in Accelerate, Nicole Forsgren, Gene Kim and Jez Humble conclude that:

External approvals were negatively correlated with lead time, deployment frequency, and restore time, and had no correlation with change fail rate. In short, approval by an external body (such as a manager or CAB) simply doesn’t work to increase the stability of production systems, measured by the time to restore service and change fail rate. However, it certainly slows things down. It is, in fact, worse than having no change approval process at all.

Oh no! The data is showing us this, but why? If I can be so bold as to put forward a hypothesis:

In 480BC the great Persian king, Xerxes, had two, large pontoon bridges constructed across the Hellespont for his army to cross the strait. A storm descended and the ocean destroyed both bridges before his army could arrive. Xerxes was so upset that he had the bridge builders beheaded (of course) and ordered his soldiers to lash the ocean with whips and brand it with red hot irons whilst shouting at the water.

A traditional cybersecurity function, ca. 450BC (That guy standing on the beach is sure there are better things they could be doing)

Your cybersecurity team can’t possibly keep up if it’s expected to assure the activities of 100 times as many people, delivering constant change that’s vital to the business’s success. The ocean, as you’d expect, doesn’t much care about your troubles.

You have two choices (ok three, but pairing every developer with their own at-desk security professional is a bit too extravagant):

- Have the development teams promise to only make minor changes without involving you and let you know when something important is changing that impacts the design of the system

- Teach the development teams to perform day-to-day assurance activities themselves and keep an eye on the aggregated output of those activities for anything missing/unusual

The first one is still a CAB, but for only certain types of change deemed risky enough. We can guess how badly expecting people to self-select themselves for a painful additional process turns out, but let’s quantify just how bad with some real numbers from one large organisation’s change control system.

Out of 18,000 code changes into production, globally, in the month analysed, 720 were reviewed by the central security team

That’s 96% of change flowing straight to production with no involvement from the central cybersecurity team. That’s a lot of “minor” changes. And the security team was absolutely swamped dealing with 720 changes in that month.

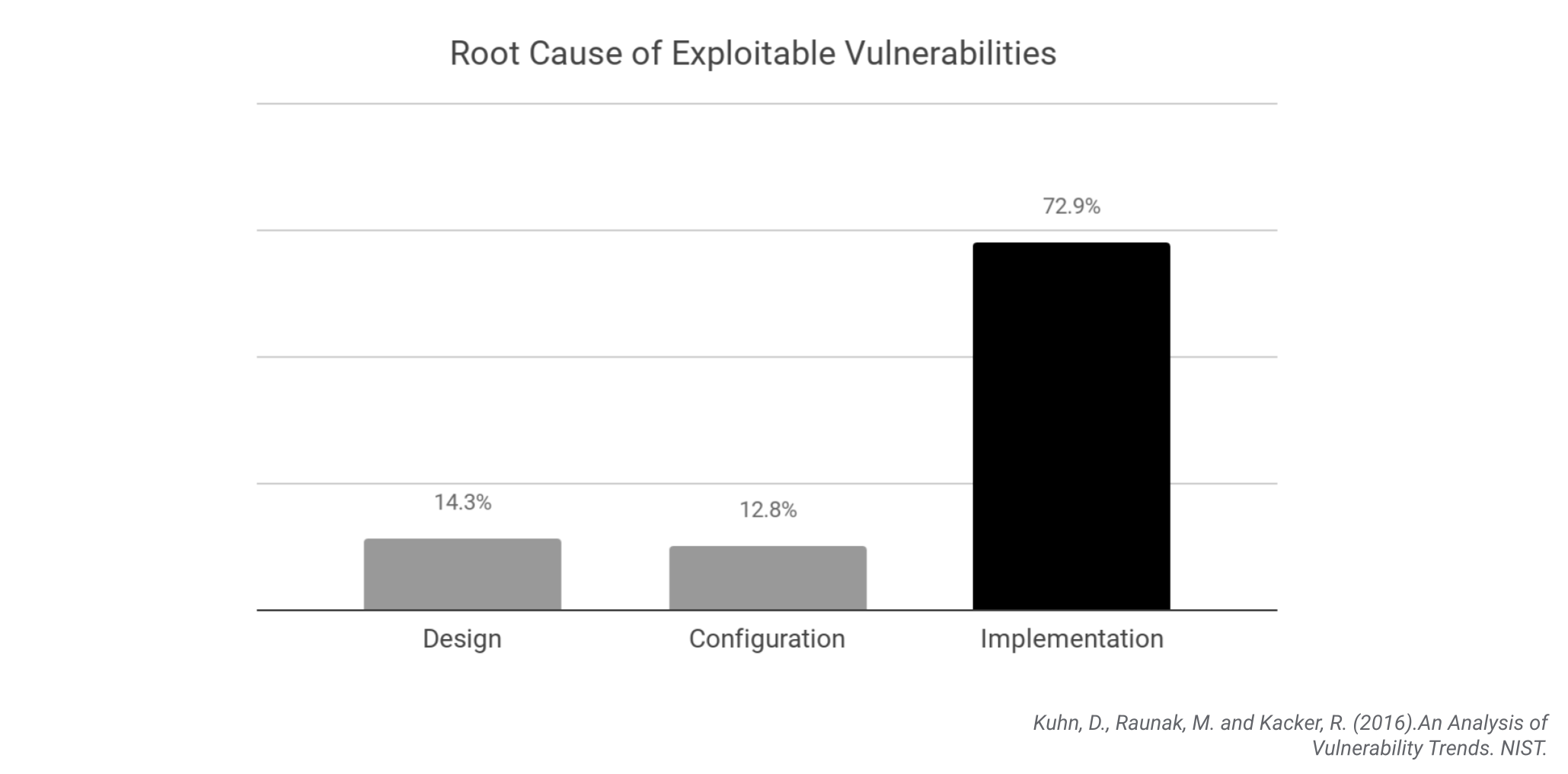

There’s also no such thing as a minor change, from a security point of view. Only getting involved when there’s a system design change ignores the majority of risk. If you’ve read my previous articles you’ll know that the root cause of 73% of software vulnerabilities in the wild is a programming error. Only 14% are caused by a design flaw.

The most dangerous type of programming error for web applications, number one on the OWASP Top 10, is introducing an injection vulnerability. A developer can introduce one (or many!) of these in an afternoon by adding a new function to a data access layer. That doesn’t warrant raising a ticket with cybersecurity, and the vulnerability can be in production the same day.

So this approach just doesn’t work. Leaving us with the second option, move these assurance activities to the people making the changes, harness the power of the ocean. Remove “The Ratio” from the process - every additional development team brings all the resources needed to perform security assurance for that team. If they have the required knowledge and the tools to do so.

- System architectures are evolutionary, constantly changing. Teach teams to perform agile threat modelling with OWASP Cornucopia as part of their release cycles to drive out new design flaws in each release

- Most of application security is in preventing security defects in code reaching production. Teach developers how to write code securely in their languages and frameworks and provide code security analysis tools for their IDEs and pipelines to catch the, still inevitable, mistakes

- Annual pentesting is way too late to catch security vulnerabilities in systems. Teach teams how to integrate automated testing tools like OWASP Zap or commercial IAST tools to continuously test and probe their systems as they are being built

- Your SOC monitors systems organisation-wide and shares threat intelligence across the industry but lacks context and in-depth knowledge of the systems. Instruct DevOps teams in secure operations and drill them with regular operational exercises simulating real cyber attacks

- Spread informed security decision-making across the organisation. Teach product owners, project managers, department heads and other key decision-makers about the fundamentals of application security and establish a common language between technical and non-technical staff

25,000 software developers are either a giant problem to be solved, or a huge resource for solving problems. Be optimistic, the glass is 99% full.

Shameless plug: Secure Delivery specialises in getting all these scaleable, modern application security practices embedded into application delivery. Get in touch with us to find out more about how we can raise your organisation’s security capabilities to ensure your teams are building the high-quality systems you need, at pace and scale.

Get in touch

We'd love to hear from you. Let's start your journey to world-class secure software product delivery today!

- Address

- Secure Delivery

Office 7, 35/37 Ludgate Hill

London

EC4M 7JN - Telephone

- +44 (0) 207 459 4443

- [email protected]